Portrait of a Legend: Tony Adams

- 4248 Views

- aksceditor

- August 13, 2016

- History

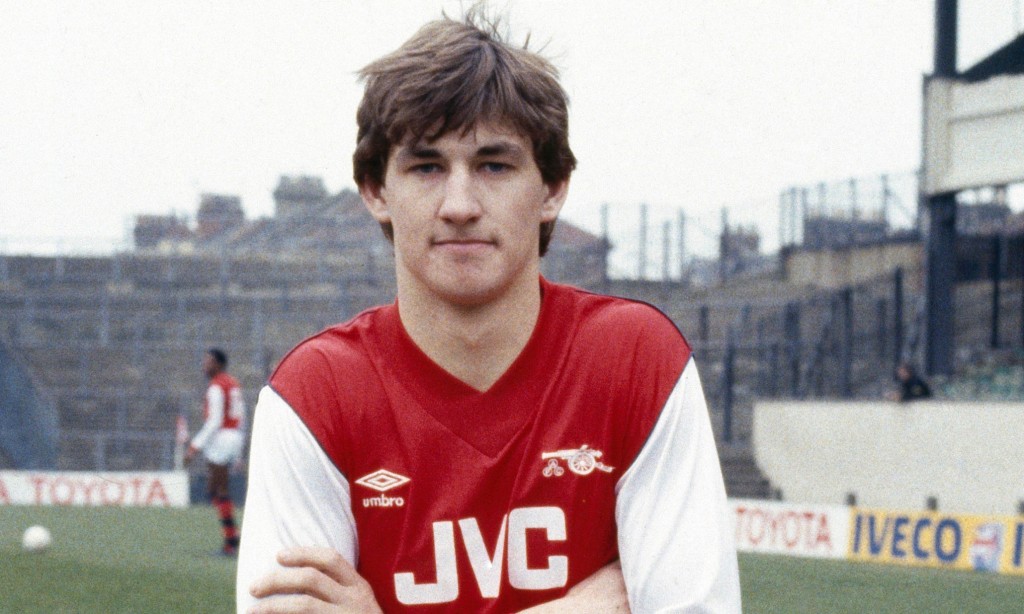

Here is a picture of Tony Adams early on in his Arsenal career, taken in late 1983 when he was still 17. His arms are crossed and his mouth is frowning, as if to demonstrate his meanness, but the eyes give away his youth and inexperience. Adam’s Arsenal shirt has an exaggerated V neck, as was the style, made by Umbro and with a sponsor (JVC) for only the second season. Behind him are the concrete steps and metal pens ubiquitous on the terraces of the 1980s. A terraced house peeps over the top of the stand, providing an illicit Saturday afternoon vantage point.

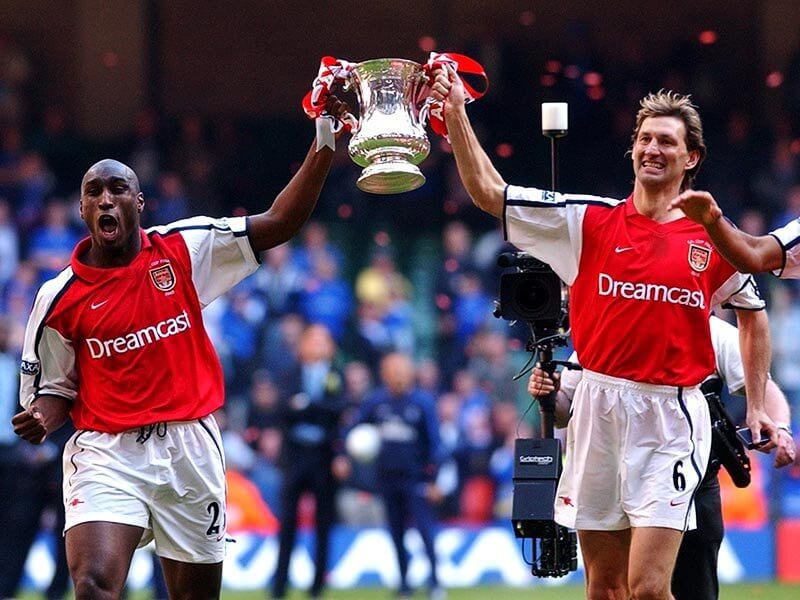

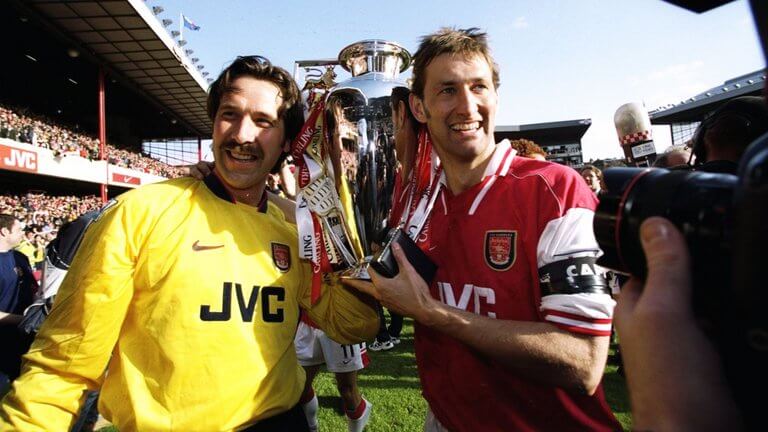

There are many more photos of Adams’ last game for Arsenal, a win against Everton at Highbury in 2002 during which the Premier League title victory – and with it the league and FA Cup double – was confirmed. Adams is pictured with Patrick Vieira and embracing Arsene Wenger in front of an all-seater, all adoring Highbury. The club badge, shirt sponsor (SEGA) and kit manufacturer (Nike) have all changed. Once the fresh-faced teenager, Adams is now Arsenal’s wizened old head. His face has been weathered first by football, but more so by life.

The length of Adams’ Arsenal service is magnificent in itself. Only David O’Leary played more games than his 669, and he remains the only league title-winning captain across three decades, having been made Arsenal’s youngest ever skipper at the age of 21 in 1988. Adams is also the only England player to make tournament appearances in three separate decades, and was the last England player ever to score at the old Wembley. He captained his country between 1992 and 1996, and won ten major honours at club level. Half of Arsenal’s post-war league titles were won with Adams wearing the armband.

Yet it is not the length of Adams’ 14-year captaincy that is so impressive, but the changes he oversaw. The defender was leader of his club through a time of great upheaval in English football, the increase in technology, commercialisation and the influx of foreign players all providing their own tests. Adams didn’t just survive amid this swirling sea; he thrived in it.

Nowhere more so were those differences noticed than at Arsenal, English football’s bellwether club, where the old-fashioned, working-class culture of Division One was replaced by the forward-thinking Premier League new world order. The progress of the English game and the advances in nutrition and sports science could be detailed purely using the case study of Arsenal’s George Graham and Arsene Wenger eras. Adams’ retirement finally marked the end of Arsenal’s ‘old guard’.

The best on-pitch leaders become the embodiment of their manager’s message, with a little of their own personality thrown in. They are essentially messengers, conduits between coach and squad but also perennially required to set the example. Rarely has that been more emphatic in English football than in the case of Adams.

Under Graham, Adams was a no-nonsense defender, the brave leader prepared to fight on the front line and get hurt for the cause; no war analogy is too much. Adams was the leader of the most efficient defensive line in English football, an organisational structure that seeped into popular culture, such was its success. ‘1-0 to the Arsenal’ was not just a chant; it was an ethos.

Under Wenger, Adams changed. After initial scepticism over Arsenal’s recruitment decision, he embraced the Frenchman’s dismantling of the squad’s extra-curricular lifestyle, again setting an example to the other players. The fire in his performances was never dampened, but Adams became a ball-playing central defender, stepping up to distribute the ball in addition to laying his body on the line when required (which was far less often). Adams’ reading of the game had always been sensational, masking his lack of pace, but Wenger fine-tuned those strengths. Wenger and Adams were the odd couple, but it was a long and happy marriage.

This multi-functionality of Adams can best be demonstrated in two quotes, from Wenger and Paul Ince. “He’s a colossus,” Ince said. “Proper centre half. Men-of-men. In our England team we were all men, we were all big characters and big men but he was men-of-men.” “Simply a professor of defence,” said Wenger. Find you a captain who can do both.

“I think Tony Adams was a United player in an Arsenal shirt to be honest with you,” said Manchester United manager Alex Ferguson. “I thought he would have been absolutely perfect for United. I tried to sign him when he was 19 and in the reserves but there was no chance.”

Adams’ skill and loyalty alone made him a fan favourite, but it was his humility and love for Arsenal made him an icon. ‘If I wasn’t playing I’d be in the stands with my mates’ is a well-versed cliche, but rings true. “Play for the name on the front of the shirt, and they’ll remember the name on the back,” is Adams’ most famous quote; remember they did.

“It’s my football club, Arsenal Football Club, and when I get an opportunity and if I’m needed and if I’m ready then I’d love to be of service,” Adams said in 2013. “When I’m needed, when I’m wanted. I’ll make the tea there!” Arsenal was – and is – in his blood.

Yet the story of Tony Adams is only partially complete by celebrating his on-field magnificence; it is also a story of depression, mental illness and addiction. The cover of Adams’ autobiography does not picture him holding a trophy aloft or embracing supporters but features a simple, close-up portrait, staring into the eyes of the reader as if using them as a mirror. The appendix begins not with his career statistics or England record, but the 12 steps of Alcoholics Anonymous. Adams is a man who has not merely come through sporting tests, but addiction, divorce and prison.

“I don’t actually like people,” Adams once told an interviewer. “I’m a loner and if I had my way I’d just walk my dogs every day, never talk to anyone and then die. I do get depressed, I’m a depressive type of guy and that’s depressing for me.” It is an emphatic reminder that addiction is not the condition as a whole, merely its most visible element. Addiction is the representation and result of mental instability and, in Adams’ case, crippling self-doubt. Alcohol became not just a drug for Adams, but a coping mechanism. At the highest level of sport, pressure becomes suffocating as your personality and reputation are constantly on parade. “There was no pleasure in anything,” Adams recalls. You drink to remember simpler times, and you drink to forget the present.

On May 6, 1990, Adams crashed his Ford Sierra into a wall when more than four times over the legal drink-drive limit. Later that year, he was sentenced to four months in prison, and served two of those. Adams still regularly visits prisons to offer advice to inmates and share the lessons he learned from his own addiction.

Even then, Adams’ problem was not managed or even highlighted. Such was alcohol’s inherent role in English football culture that many supposed Adams had simply paid the price for having too much on a night out. The fabric of football in the 1970s and 1980s initiated alcohol dependence, and then promptly allowed the problem to fester. Some could take it or leave it, but others were not so lucky; they never stood a chance.

There was a bleaker reason for Adams’ alcoholism to stay hidden. In some circles, depression is a modern phenomenon. To reveal your mental illness in the testosterone-charged world of the Division One changing room would have been a concession or admission. Even those recent sufferers (cricket’s Marcus Trescothick and Jonathan Trott are good examples) are treated with an air of suspicion, as if depression is an easy excuse rather than a debilitating, and potentially life-threatening, illness.

Thankfully, attitudes are changing. There is an odd dichotomy whereby every new publicised case is incredibly sad for the individual, but good for the greater understanding of the condition. Unfortunately for Adams, to have revealed his illness in 1990 would have been to risk stigmatisation and thus his entire career.

It was September 1996 when Adams announced his alcoholism publicly, and revealed that he had sought treatment. He became one of the most high-profile addicts of his time, speaking of his new-found love for Shakespeare and the piano. Five years later, and Adams was still leading Arsenal as they entered a double-winning season. A career and a life had been saved.

At a time when too many people still believed that fame, fortune and sporting success was a blanket against depression rather than a factor in it, it took an awful lot to be revered by the masses despite his condition. By merging sporting success, addiction rehabilitation and mental illness, Adams became the poster boy for recovery.

Not only that, but Adams understood the impact his redemption could have, if utilised appropriately. He saw the need for a dedicated environment where sportspeople could address and manage their mental instabilities, from the comparatively manageable to the life-limiting and destructive, while young athletes would be given proactive education to spot the danger signs. In 2000, he formed the Sporting Chance clinic.

“Sporting Chance is absolutely up there with all the medals I’ve ever won, the England cap and everything,” says Adams. “I’m very proud of what I created here.” And so he should be. Kenny Sansom and Dean Windass are just two former players who believe that the clinic saved their lives.

“You’re talking about a man who could drink and get pissed,” Adams said in an interview with the Irish Independent. “I had no self-esteem. I had suppressed every emotion in booze. I didn’t know who I was. I didn’t know how to handle life, sex, everything. I had to learn absolutely everything, I was a child again so when I sobered up I got to know myself.” That he did all that while serving so magnificently as Arsenal captain shows incredible resolve and strength of character, but is also a testament to his natural talent as a central defender.

If it seems demeaning or uncharitable to focus on Adams’ off-field issues during a celebration of his iconic status, I take my lead only from the man himself. The final paragraph of his autobiography marries the two together:

‘My views on winning have changed a lot,’ Adams writes. ‘Today I am not just Tony Adams the footballer, I am Tony Adams the human being. I do my best to treat myself and other people with respect. In that there is also victory. Winning on the field is sweet, of course, but in addition, as far as I’m concerned, with each day that I do not take a drink, I will always be a winner.’

And, for as long as his beloved club play in red and white, Adams will always be an icon. He is the true ‘Mr Arsenal’.

by Daniel Storey