The Coronation of the King – by a hardcore rival fan

- 1027 Views

- aksceditor

- August 26, 2016

- History

by Matt Gault (Manchester United supporter since forever)

Growing up as a Manchester United fan in the era of the Arsenal Invincibles, I perhaps would have been excused for despising Thierry Henry. The Frenchman was the archetypal player to strike fear into the hearts of young fans of opposing teams like myself. However, as I continued watching United and Arsenal battling for Premier League supremacy year after year, I softened to Henry’s charm. His panache, infinite coolness and immeasurable talent only made him an endearing character to me, despite the colours he adorned. It was undeniable: Thierry Henry was mesmerising to watch, no matter where your allegiances lay.

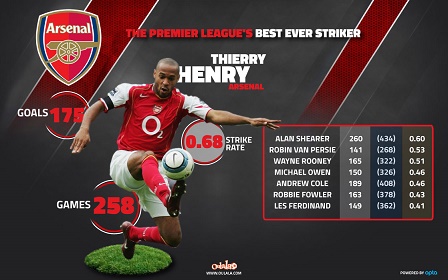

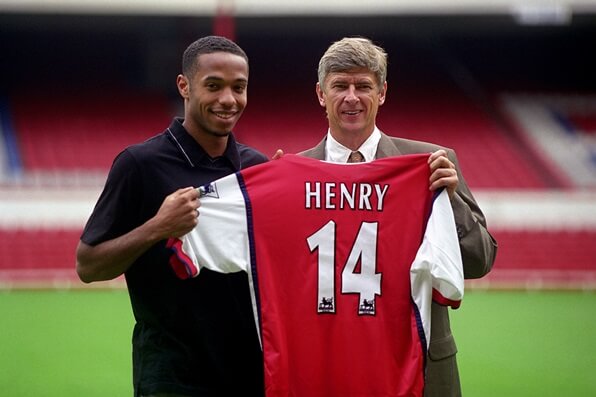

During his illustrious career, Henry became the all-time top scorer for both France and Arsenal, won two Premier League titles with the latter, a World Cup with the former, as well as the Champions League, two La Liga titles and the FIFA Club World Cup amongst a galaxy of individual accomplishments and plaudits. He also had spells with AS Monaco – where he started his career – Juventus and the New York Red Bulls, where he retired in 2014. However, it was his eight years as the ‘High Priest of Highbury’, (later the ‘Emperor of the Emirates’), that made him a footballing legend. Signed by Arsène Wenger in 1999 after a frustrating stint in Serie A with Juventus, Henry exploded onto the English football scene to eventually become arguably the Premier League’s greatest ever player.

It all began for Henry in Ligue 1, where he rose through the ranks at AS Monaco to make his professional debut in 1994. Henry was educated in the elite French football academy of Clairefontaine before he joined Wenger’s Monaco as a fully-fledged professional. Wenger anointed Henry as a winger as he believed his pace, close control and skill could make him an effective piece of attacking artillery in that position.

In the principality Henry blossomed into a player of sublime quality and was instrumental in Monaco’s 1996-97 Ligue 1 triumph. Of course, his reward for conquering the domestic sphere in France was the opportunity to exhibit his prodigious talents on a greater platform: the UEFA Champions League. In the 1997-98 campaign, Jean Tigana’s Monaco surprised many by reaching the semi-finals, thanks in no small part to Henry’s seven goals. It was the young Frenchman’s rapidly improving firepower that thrust Monaco to new heights and to the highest stratums of European club football.

By his 21st birthday, Henry had officially announced himself on the highest stage in European club football and established himself as one of the hottest prospects in the world. The sky was the limit for the gifted winger from Les Ulis on the outskirts of Paris, who had already achieved more than any other French player of his generation by such a young age. Named France Football’s Young Player of the Year, Henry also collected a European title with the France under-21 and earned a call-up to the senior squad from national manager Aimé Jacquet.

His integration into the Les Bleus set up was a surprise to many, but Henry remained entirely unfazed by the magnitude of representing his country at a home World Cup. Jacquet took the last-minute decision to include a 20-year-old Henry in his final squad in favour of Nicolas Anelka, who had broken through in spectacular fashion that season with Arsenal.

Henry grasped the opportunity to impress once again, finishing France’s greatest ever tournament as top-scorer with three goals. Although he did not feature in the 3-0 final triumph over Brazil – he was poised to come on as a substitute before Marcel Desailly’s red card prompted a defensive move instead – Henry’s group stage goals helped propel his country to within touching distance of football’s ultimate prize.

Henry’s progression and development was strongly abetted by his experiences in the World Cup but he became out-of-favour at Monaco after he returned to club football as a world champion. Wenger had attempted to lure the coveted star from Monaco to Arsenal after the World Cup but was met with a firm rebuttal. It was widely known that Henry would have favoured a reunion with Wenger but he was powerless as Monaco sought to hold on to their prized possession. As a result, Henry’s dip in form was associated with the idea that he no longer felt his heart was in Monaco. He was subsequently transfer-listed and a move away from his first professional club was edging closer to reality.

Then, his career threatened to spiral into the abyss of obscurity after he made the switch to Italy and one of Europe’s most distinguished clubs in Juventus. Under Marcello Lippi first and later Carlo Ancelotti, Henry failed to impress during his half-season with the Italian giants and the experience of either being played out of position or not playing at all haunted the Frenchman. A dream move to one of Europe’s top clubs had not materialised into the fairy tale Henry had envisaged and it only served to hinder his advance to sporting superstardom.

He had joined up with French teammates Emmanuel Petit, Didier Deschamps and Zinedine Zidane at Italy’s Old Lady but Henry was unable to cement his place in the first team in Turin during what was perhaps his most frustrating season in professional football. Henry’s burgeoning brilliance was blunted by his painful adaptation to a tactical system which favoured defensive duties under Ancelotti. In Italy, he was neither a flying winger nor a predatory finisher. He was instructed not to neglect his defensive duties but Henry’s natural instinct was to go forward, not back, and it was for this reason that Gianluca Zambrotta usurped him in the pecking order.

Sometimes in football, the paths of the great are pre-ordained and fate was not about to let Henry fade into the obscurity in Italy as an old friend extended an arm and sanctioned the move that would change Henry’s life forever.

Wenger had been the coach at Monaco during Henry’s baptism into the professional game and the two had maintained an amicable relationship after Wenger had moved to North London to replace George Graham as the new Arsenal manager. Wenger had pushed hard to sign Henry before he eventually moved to Juventus but the Gunners’ manager remained patient and bided his time for the next opportunity. When it came, he grabbed it with both hands and the two never looked back. Henry was disillusioned with life in Italy by the time Wenger had decided to revive his interest in the player and the transfer to Arsenal was a more serene process than Wenger’s endeavours a year earlier.

So began the great metamorphosis at Highbury from a frustrated winger to one of the most feared attacking talents of his generation. Henry had been partly persuaded by the strong French stable in North London like Petit and Patrick Vieira, who had given him shining reports of the club and its fans, not to mention the experience of playing in the Premier League.

Arsenal had been crowned champions in 1998 but were edged out by Manchester United a year later on the final day, so overhauling their Mancunian nemeses was the primary objective. Firmly established as a force in English football, Arsenal turned to Henry to continue their age of excellence into the 21st century. Although Henry never had the opportunity to form a deadly partnership with Anelka – who left Arsenal in a high-profile transfer to Real Madrid that same summer – he comfortably managed to uphold, then surpass his predecessor’s legacy at the club in becoming its greatest ever player.

Henry became synonymous with Arsenal’s aura of invincibility as they screamed past Manchester United to become the dominant force in the Premier League. The Frenchman was one of several shrewd acquisitions made by Wenger as he set about building one of the most impressive squads in modern football, blending experience and youth, foreign imports with home-grown talents, to forge a team of glorious potency and incomparable chemistry. With a rock solid core of players already settled at the club like Vieira and Dennis Bergkamp, the influx of Henry, Freddie Ljungberg and Robert Pires transformed Arsenal from a good side challenging for the title, to an indomitable force that managed to complete an entire season unbeaten in 2003-04. Central to Arsenal’s pre-eminence during that period was a Thierry Henry operating at his maximum potential.

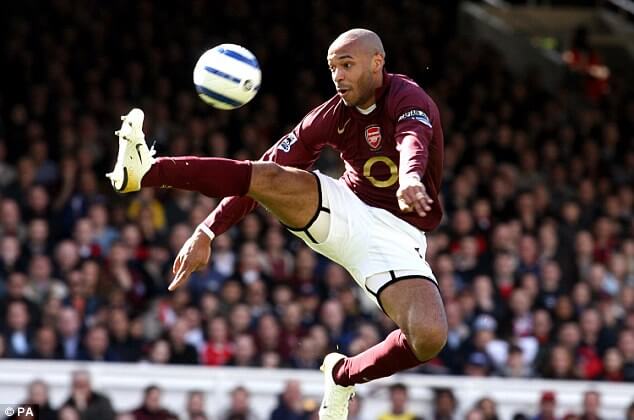

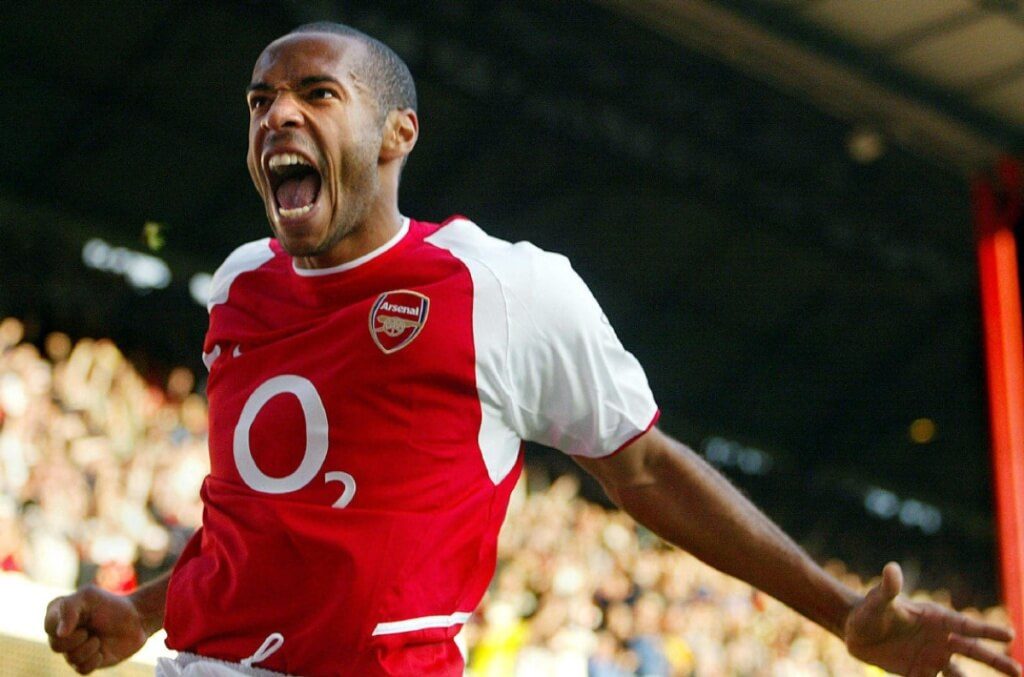

During Arsenal’s rise, Henry was a king, a peerless attacking talent who consistently buttressed the argument that he was the complete player. Already a lethal finisher, Henry also possessed that rarest of quality; running at full speed with the ball at his feet. Like a young Ryan Giggs, he became virtually unstoppable when he flooded forward in full flight. Elegant but deadly in equal measure, it was a hallmark of his play to elude defenders before slotting the ball neatly into the far bottom corner.

While analysing a game at the World Cup in Brazil for the BBC, Henry admitted that he tried to finish the same way every time he found himself bearing down on goal – to side-foot the ball with a considerable degree of power but with an emphasis on finding the corner. It was a technique that served him well during his haul of 228 for the Gunners, making him the club’s greatest marksman of all time.

The French wizard was the type of player who could produce moments that simply transcended expectations and exhausted superlatives. His incredible panache for the spectacular, the outrageous and the improvised, highlighted his brilliance and gave the impression that we were indeed watching a master craftsmen at work. A simply awesome flick and volley on the turn over the head of French teammate Fabien Barthez against Manchester United is one that still resonates strongly even today, well over a decade later.

His missile-esque long-range strike against Manchester City was the perfect example of how a ball could be struck, while his cheeky back-heeled piece of artistry illustrated eloquently just how soaring his confidence could be during a gloriously fruitful period for the Gunners between 2001 and 2005 when he was unquestionably the most breathtaking player to watch in English football.

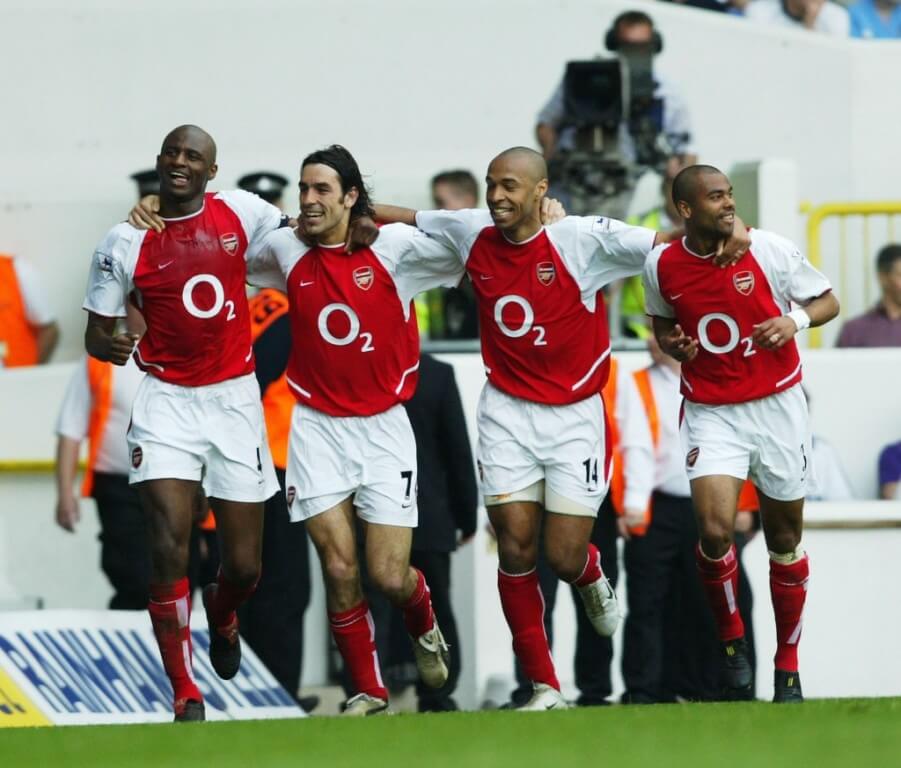

Of course, one of the greatest aspects of Henry’s all-round game was just how well he played as part of a team. Arsenal’s Invincibles were built on a team of great skill, confidence and chemistry, and Henry blended in seamlessly amongst the ocean of talent on display in North London.

His understanding with Robert Pires was telepathic at times while he was never far from being on the same wavelength as fellow striker and Arsenal legend Dennis Bergkamp. It was this aspect that made him utterly indispensable and immensely popular with the fans. His sheer talent aside, Henry emphasised the importance of operating efficiently within a unit of eleven players and this stood at the centre of what he held dear in football. At once, an extraordinarily gifted showman and a leader in a mightily impressive band of players.

Henry achieved everything in domestic football at Arsenal but he craved Champions League glory and this pursuit, burning deeper than ever after losing out to Barcelona in the final of 2006, prompted his eventual departure from the club a year later, moving to the Catalan giants to join the Pep Guardiola revolution.

Henry scored nineteen goals in his first season at the Camp Nou, helping his new side to a glorious treble in 2009 when they defeated Henry’s old foe Manchester United in the final in Rome. That time in his career was notorious for his exploits outside of Camp Nou, with a disgraced moment of handling the ball to force France’s entry into the 2010 World Cup at the expense of Ireland. The fallout from that incident was enormous and Henry was the first to admit that he regretted his decision. He conceded that it was unfair on Ireland, who had held their own over two legs against France and that replaying the playoff match would be the only fair conclusion. Unfortunately, FIFA declined Ireland’s request for a re-staging of the match and Henry was left to live with a blemish on his career and a mark against his character.

He toyed with the idea of retiring from the game he loved following that incident but instead endured the misery of his country’s disastrous World Cup campaign where they were eliminated in the group stage and the team was ripped apart by internal discord led by a player revolt against manager Raymond Domenech.

Partly disgraced, partly humiliated, Henry bowed out of the international scene as the second-most capped player in France’s history behind Lilian Thuram. There were, at times, criticisms levelled at Henry that he did not produce a similar level of spectacular play for his country as he did at club level but on the face of it, such claims are entirely wide of the mark. Integral to their World Cup success in 1998, and even more so during their march to Euro 2000 glory, Henry was also a pivotal member of the squad that finished runners-up to Italy in 2006.

It is perhaps the case that he achieved everything on the international scene as well as for his clubs, a feat which is often considered the defining point in deciding who the greatest players of all time are. Not many can argue that Henry stands tall in that category. His brilliance will always be remembered. His genius will always live on.